PRESSURE: Fish Passage

![]() More than 1,345 dams impound water in Washington State,33 including about 145 large dams owned or regulated by the federal government. Hydropower dams block large areas of former salmon habitat, particularly in the Columbia River basin, where thousands of miles of spawning and rearing habitat are blocked in the watersheds of the upper Columbia and Snake Rivers.

More than 1,345 dams impound water in Washington State,33 including about 145 large dams owned or regulated by the federal government. Hydropower dams block large areas of former salmon habitat, particularly in the Columbia River basin, where thousands of miles of spawning and rearing habitat are blocked in the watersheds of the upper Columbia and Snake Rivers.

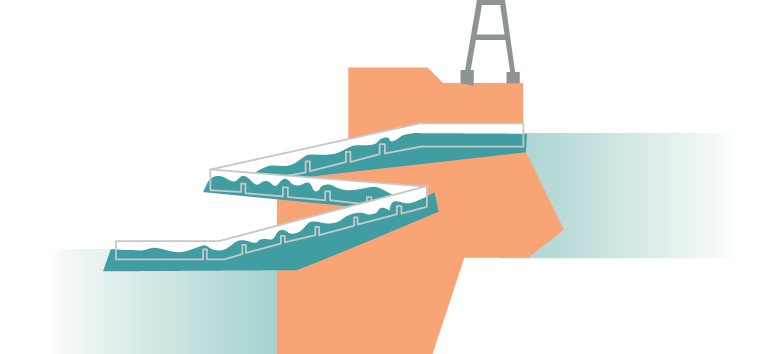

Most hydropower dams in Washington allow fish to pass upstream and downstream of the dam, using fish ladders or bypasses, or by trapping and hauling fish by truck or barge. These methods have had varied success; adult migration through fish ladders generally is effective, for example, while juvenile salmon traps in reservoirs have struggled to meet their goals. Inefficient fish passage systems reduce the number of adults migrating upstream and can delay or prevent juveniles from moving downstream.

Fish ladder at the John Day Dam on the Columbia River

Fish ladders, below, are a series of gradual steps that enable fish to swim around or over a dam. Ladders are in place at all federal projects on the lower Columbia and lower Snake Rivers.

PRESSURE: Upstream and Downstream Effects

Dams interrupt river systems: they slow and often warm water in reservoirs, block gravel and large wood movement, disrupt beneficial floods, and inundate spawning and rearing habitat.

PRESSURE: Predation

Dams delay migration upstream and downstream and can concentrate fish in small areas on either side of the dam, making them likely to be eaten by waiting birds, seals, and sea lions. Reservoirs behind dams also create ideal habitat conditions for native and non-native predatory fish such as northern pikeminnow and smallmouth bass that gobble up young salmon.

PROGRESS AND PRIORITIES

![]()

Columbia River Basin Reform

Several recent high-profile efforts have focused on restoring Columbia River salmon and steelhead. In September 2022, the National Marine Fisheries Service released Rebuilding Interior Columbia Basin Salmon and Steelhead,34 a report outlining major actions that the agency believes necessary to achieve mid-range goals for 16 salmon and steelhead stocks that spawn above Bonneville Dam, including large-scale reintroduction and breaching of the lower Snake River dams.

Separately, Governor Jay Inslee and Senator Patty Murray released the final Lower Snake River Dams: Benefit Replacement Report35 in August 2022, detailing the costs of replacing services provided by the four lower Snake River dams. Many experts have concluded that the most impactful salmon recovery action in the region includes removing or bypassing these dams, improving fish passage, eliminating water quality impacts, and reestablishing spawning areas, particularly for Snake River Chinook and steelhead populations. The dams provide power, navigation, irrigation, and recreation services that Governor Inslee and Senator Murray recognize must be replaced before breaching or bypassing the dams.

Reintroduction

Fish passage technologies have improved, and salmon reintroduction efforts are underway in many watersheds that have been inaccessible for nearly 100 years, such as the upper Lewis, Cowlitz, and Green Rivers, and the Columbia River above Grand Coulee Dam. In some areas, such as the Elwha, Middle Fork Nooksack, Pilchuck, and White Salmon Rivers, dams have been removed, greatly benefiting salmon.

Improved Downstream Migration

Hydropower managers recently have changed how much water is directed over dams in the Columbia and Snake Rivers, rather than through electricity-generating turbines, to benefit salmon. Known as spill, these flows have sped juvenile migration to the ocean and increased their survival by avoiding turbines.

In the Elwha, Middle Fork Nooksack, Pilchuck, and White Salmon Rivers, dams have been removed, greatly benefiting salmon.

Banner photograph of Ross Dam in Whatcom County courtesy of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Photograph of the John Day Dam by Karim Delcado

Photograph of the cormorants by Sondra Ruckwardt, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Photograph of the Elwha River courtesy of NOAA Fisheries