Barriers to Migration

Salmon spawn (reproduce) in cool freshwater streams. Some spawn close to saltwater, while others swim more than a thousand miles through rivers and streams to reach their home waters. After emerging from their nests in streambed gravel, coho salmon, steelhead trout, and some Chinook salmon spend months or years in freshwater, sometimes traveling upstream from their birthplace to very small streams to find food and habitat. When they are ready, they proceed downstream until they reach the ocean, where they grow to adult size. People have interrupted these migrations in many ways. Barriers to fish migration, especially dams and road crossings, are some of the most visible ways that people have blocked salmon migration.

PRESSURE: Aging Road Crossings and Dams

![]() Many areas that used to be salmon habitat in Washington today are blocked by roads, dams, railroads, and water diversions for farms. The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife estimates that at least twenty thousand barriers either partially or fully block salmon from reaching their spawning grounds in Washington.1

Many areas that used to be salmon habitat in Washington today are blocked by roads, dams, railroads, and water diversions for farms. The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife estimates that at least twenty thousand barriers either partially or fully block salmon from reaching their spawning grounds in Washington.1

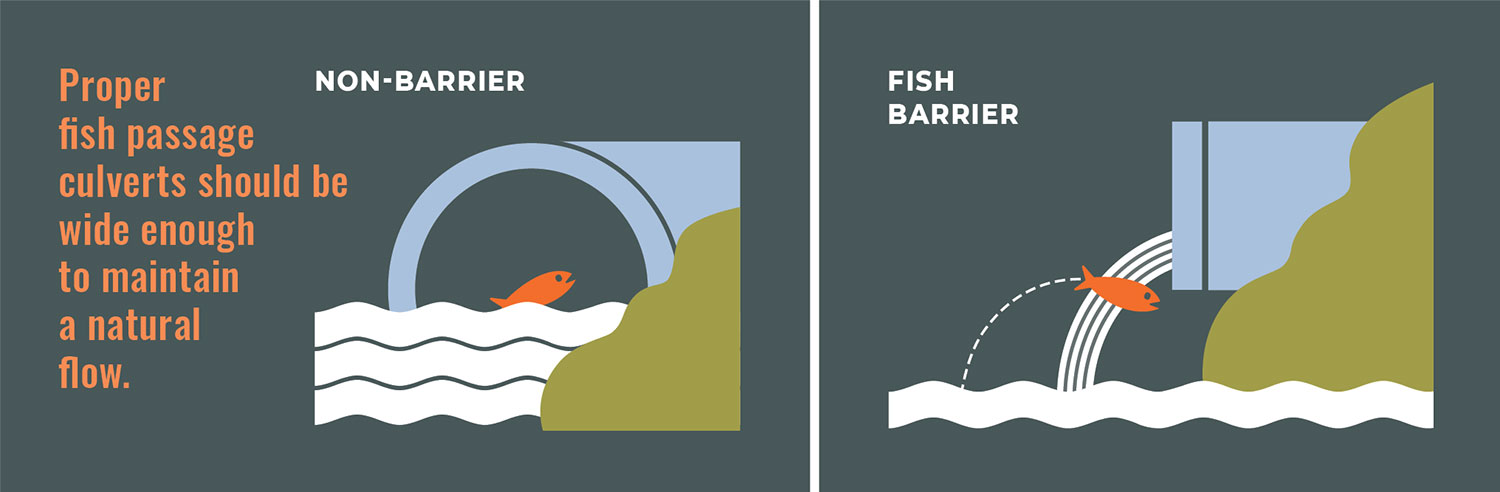

Most barriers were created when roads crossed streams, forcing streams into pipes known as culverts. Poorly designed culverts often block fish from swimming upstream. Coho and steelhead are affected the most because they travel further upstream to spawn, and young coho salmon often move upstream and downstream to find food.

Levees and elevated roadbeds also can prevent fish from swimming into side channels of rivers, which are important areas of calm water where young salmon grow.

PRIORITIES AND PROGRESS

Statewide Tracking

Statewide Tracking

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife maintains a database of fish barriers, fish use, and habitat information throughout Washington State. The department’s database is the main source of information for planning fish passage projects. This database is comprehensive, but more work is needed to identify barriers, especially small barriers on private lands, many of which may be eligible for grants to fix.

Grant Programs

Washington State has recognized the need to correct fish passage barriers and has several efforts underway including work funded by the Brian Abbott Fish Barrier Removal Board, Family Forest Fish Passage Program, and Salmon Recovery Funding Board. Newly approved state and federal infrastructure spending also is promising to address fish passage barriers, especially on roads that need to be improved for safety. Since 2005, more than 3,866 barriers have been corrected using grants managed by the Recreation and Conservation Office, reopening more than 5,100 miles of habitat to salmon and steelhead.

Forest and Fish Law

Under the 1999 Forests and Fish Law, private landowners and state forest managers in Washington have corrected more than nine thousand barriers, including many that are higher in watersheds than salmon or steelhead travel.

Culvert Injunction

In 2001, twenty-one western Washington Tribes, represented by the federal government, sued Washington State for its failure to correct fish-blocking culverts, arguing that the state-owned barriers damaged their treaty rights to harvest fish. In 2013, the U.S. District Court issued an injunction requiring four state agencies2 to correct barriers by 2030, which likely will cost more than $7 billion. Three of the four state agencies have completed their required work by removing 177 barriers and opening about one hundred miles of habitat. As of June 2024, the fourth agency, the Washington Department of Transportation, had fixed 146 barriers, opening more than 571 miles of habitat for salmon.3 The agency plans to complete fixing fish-blocking culverts by 2030.

Since 2005, more than 3,866 barriers have been corrected, reopening more than 5,100 miles of habitat to salmon and steelhead.

1Washington State Fish Passage web page. https://geodataservices.wdfw.wa.gov/hp/fishpassage/index.html Accessed August 23, 2024

2Washington v. United States (Supreme Court of the United States, 17-269, 2018) https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/17pdf/17-269_3eb4.pdf.

3WSDOT Fish Passage Performance Report, 2024. http://www.wsdot.wa.gov/construction-planning/protecting-environment/fish-passage. Accessed November 4, 2024